The following article originally appeared on the The Source blog on May 20, 2013.

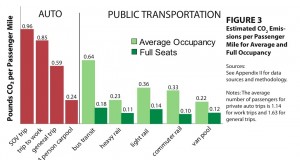

One of the arguments frequently made for building more mass transit — in particular rail projects — is that it will help reduce pollution and, as a byproduct, greenhouse gases that are contributing to climate change. The above chart comes from a Federal Transit Administration report updated in 2010 that considers the impacts of cars versus transit. Although in some circles this remains a disputed issue (mostly by critics of rail transit), the FTA finds transit is the clear winner.

Comparing the emissions of cars versus transit is not always a clear-cut issue because of the number of variables involved. Which brings us to a new study by several UCLA researchers that drills down deeper on the subject by comparing the Orange Line, Gold Line and average automobile in Southern California. The study was published in Environmental Research Letters and is posted below.

The study found that in both the near term and long-term, the Orange Line and the Gold Line produced less smog and greenhouse gases than the average auto driven in L.A. County. In addition, the Orange Line and Gold Line used less overall energy than cars and will create less particulate matter than cars in the long-term, although the Gold Line currently produces about the same as cars, due mostly to its electricity coming from coal-fired power plants used by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

Four key points from the new study:

•Both cars and transit are expected to get cleaner over time as fuel mileage increases for cars and transit relies on cleaner energy sources, i.e. solar, wind, thermal and natural gas.

•Construction remains a big challenge for transit projects because things such as pouring concrete and the use of heavy equipment tends to result in high emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollution — and it can take years, if not decades, for transit to make up for the big cost in terms of greenhouse gases made up front.

•Transit vehicles spend far less of their time parked than cars, which spend 95 percent of the time sitting around. That means that the energy and emissions needed to manufacture, transport, and park transit vehicles are spread over a lot more passenger miles and hours of operation.

•Transit needs to shift 20 percent to 30 percent of its riders from cars to transit order to have less impacts than cars and, as the study says, “the larger the shift, the quicker the payback” when it comes to meeting environmental goals.

Left, Getting people out of their cars onto trains is crucial to improve efficiency of transit. Photo of Expo Line by Steve Hymon/Metro.

I think that last point is crucial for policymakers. To put it another way: if transit agencies and politicians want transit projects that truly improve air quality and such, they have to build projects that will appeal to motorists and pry them out of their cars.

It’s always difficult to compete with the door-to-door convenience of the automobile, but I think it’s do-able but it means building projects that stop where people want to go, making it easy to get to and from stations by car, foot or bike and either designing projects that are fast and/or operate frequently enough to reduce the time-munch that is standing around and waiting at a station.

One other point: earlier this month, it was reported that levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere probably haven’t been this high in the past three million years. Carbon dioxide is a primary greenhouse gas and it’s a byproduct of burning fossil fuels for things such as transportation, heating, construction etcetera. Seems to me that transit agencies across the world — many of which shun being political — could market transit as a way to help people perhaps make a difference when it comes to climate change.

Sermon over. The study is below. Kudos to Mikhail Chester, Stephanie Pincetl, Zoe Elizabeth, William Eisenstein and Juan Matute for putting this together. Finally, Metro issues an annual sustainability report that details its efforts to reduce greenhouse gases used by the agency’s transit vehicles and facilities. In fact, Metro cut its greenhouse gas emissions five percent between 2007 and 2011, the last year numbers are publicly available.