The following article appeared in CityLab on January 12, 2015.

What Does Living ‘Close’ to Transit Really Mean? – CityLab

New studies suggest proximity to transit is quite flexible and could extend to a mile out.

By Eric Jaffe

January 12, 2015

The question of how far people will walk to reach a transit stop has a pretty significant impact on the shape of cities. American urban planners conventionally draw that line at about a half-mile. Some guidelines pull it back to a quarter-mile, while others adjust the distance for bus stops (typically a quarter-mile) and train stations (typically a half-mile), but the consensus holds that no one makes it farther than half a mile that on foot.

The impact of this thinking can be seen clearly in the planning rules a city creates for its transit-oriented development. Take two recent examples: Denver just started a fund to help finance properties built within a half-mile of light rail and a quarter-mile of good bus stops, and the town of Mamaroneck in metro New York just zoned for TOD within a quarter-mile of its commuter rail station. Even as such guidelines encourage urban growth, they also establish a hard edge for it.

New research, set to be presented Monday at the 94th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, suggests that some cities indeed might be selling their TOD footprint short. A study group led by planning scholar Arthur Nelson of the University of Arizona analyzed the impact that proximity to a light rail station had on office rents in metropolitan Dallas. They found that a quarter of the rent premium (“not a trivial amount,” they submit) extended nearly a mile away from transit.

“I recommend this [a mile] as the TOD planning area for office and related land uses,” Nelson tells CityLab.

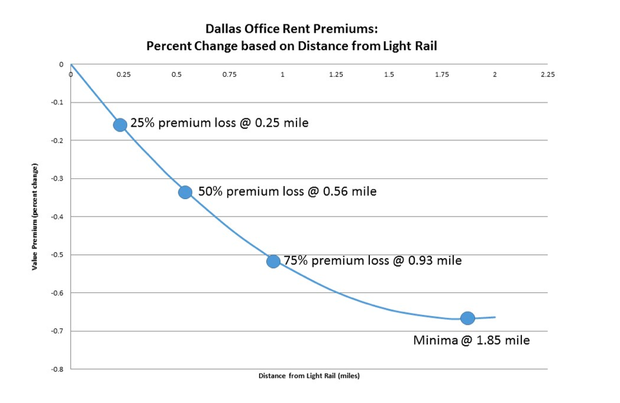

As expected, Nelson and company found that rent premiums decreased farther away from a DART station. A quarter of the premium disappeared after a quarter-mile, half disappeared at about .56 miles, and 75 percent had disappeared by .93 miles (below). But that means a quarter of the rent premium extended almost a full mile away from transit—and the researchers detected evidence of a premium as far away as 1.85 miles from light rail stations.

The findings echo a similar analysis recently conducted in the Twin Cities. For this study, two University of Minnesota scholars analyzed the values of commercial and industrial properties along the metro area’s 12-mile, 19-station Hiawatha light rail line. In a 2013 paper, they reported a transit-oriented price premium that extended nearly nine-tenths of a mile from the light rail stations:

This suggests that future studies that assess property value effects should go beyond the traditional 1⁄4-mile and 1⁄2-mile buffers while imposing some form of boundary limitations. Such a refinement on the study area of transportation investment can help reconcile the differences in the size of impact area of transit voiced by various stakeholders, especially in applications for federal and state funding such as TIGER or in developing financing instruments such as TIF.

What both these studies point to is that “proximity” to transit is a rather flexible setting that’s by no means limited to a quarter- or half-mile in all cases. Of course, most people prefer to walk as little as possible to reach a transit stop or station. But not all urban street networks are created equal (walking a half-mile in Manhattan doesn’t feel the same as walking that far in, say, pedestrian-unfriendly Orlando) and not all riders have the same options. The recent findings at least raise the possibility that cities could increase both ridership and market opportunities by extending TOD planning at least a mile from a station.

And the impact of transit proximity bears on more than planning zones. Acceptable walking distance can inform value capture arrangements that help cities recoup real estate premiums generated by transit access. It can also influence the frequency of a transit system itself: if you assume people will walk farther to bus stops, for instance, you can set these stops farther apart, thereby reducing operating costs using the extra money on more buses.

So it’s tricky to determine just how far people will walk for good transit. But doing so is hardly trivial.